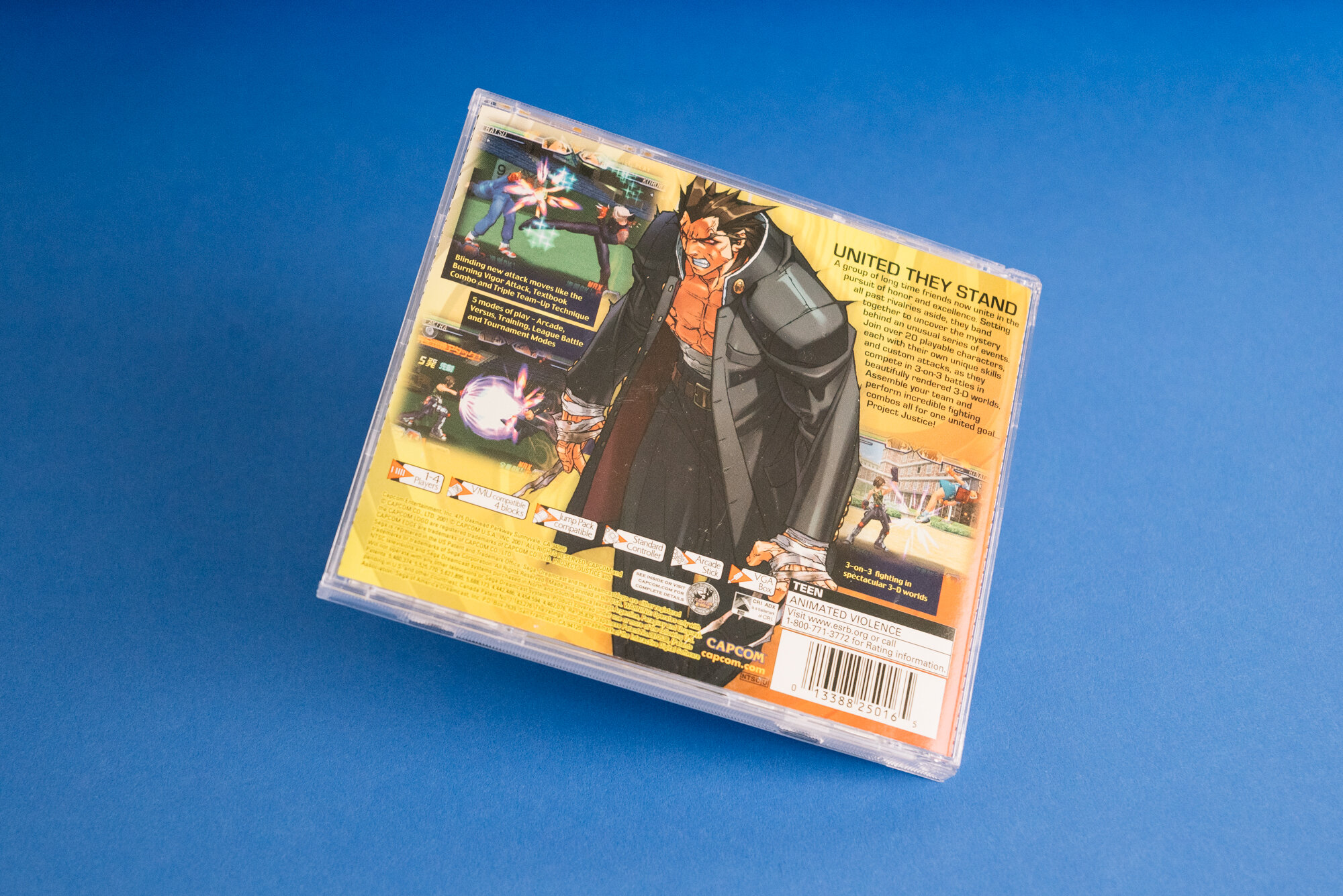

Project Justice (Rival Schools 2)

Developer - Capcom

Publisher - Capcom (Japan, North America); Virgin Interactive (Europe)

Director - Hideaki Itsuno

Composers - Yuki Iwai, Etsuko Yoneda, Setsuo Yamamoto

Genre - Fighting; up to four players

Dreamcast Release Dates - May 16, 2001 (North America); December 17, 2000 (Japan); April 13, 2001 (Europe)

Additional Releases - SEGA NAOMI arcade cabinet (2000)

Current Average Price - between $300 and 400

I can’t say that Project Justice (Rival Schools 2) is the best fighting game on the Dreamcast. Different games for different tastes, after all. But I can say with confidence that it’s my personal favorite.

The game’s characters, story presentation, and fighting systems are excellent and unique to those of any other fighting game on the console. The music is fantastic. The stages are varied and interesting. The art direction and character models are vibrant and alive, and the controls are fast and responsive. Project Justice is a real gem, sparkling with personality, and it’s truly a shame that more than twenty years have passed without any further games in this series.

Origin of Project Justice

Project Justice is the sequel to Rival Schools: United by Fate, a 3D fighting game originally released in arcades in 1997 and later ported to the Sony Playstation in 1998. This original game and its sequel are often described as a 3D polygonal Marvel vs. Capcom, a characterization which is reductive and lazy. Rival Schools and the subsequent Project Justice have their own identities and personalities. They are their own games, and they deserve retrospection beyond others of Capcom’s franchises.

The series was developed initially when game designer Hideaki Itsuno decided to develop a new 3D polygonal fighting game. This would be just the second ever 3D fighting game developed by Capcom, after 1996’s weapons-based fighter Star Gladiator. The technical goal was to create a 3D fighting game capable of running at 60 frames per second - this in response to Star Gladiator’s capped 30 FPS.

The original title for this new 3D fighter was Justice Fist, and featured a somewhat pedestrian story in which fighters from countries all over the world came together to decide who was the strongest. After this original concept received a lukewarm response within Capcom, Itsuno decided to base the game’s story, settings, and characters on something which normal people could relate to - school. Thus Rival Schools began to take shape.

The original intention was to create a game in which forty characters competed in martial arts to determine who would be the class representative. Later, when a programmer showed him multiple characters appearing as playable fighters on-screen at once, Itsuno created the idea of a two-person team battle fighting game. This team-battle system and the school setting ended up becoming the core concepts of Rival Schools and Project Justice.

Set within the same universe as Capcom’s Street Fighter, the original Rival Schools featured the popular Street Fighter character Sakura Kasugano.

Project Justice Gameplay and Game Design

Like its predecessor, Project Justice is a team-based 3D fighting game wherein the player controls more than one fighter. But PJ pushes this mechanic even further. Where Rival Schools features two-person teams, Project Justice bumps it up to a three-person team. Because of this change, many new gameplay elements emerge in PJ. There are now two distinct Team-Up attacks (in which the player calls on one of their teammates to deal damage or otherwise influence the fight), and a new Party-Up attack (in which the player calls on both teammates to join in with a massive damage-dealing power move).

There’s another new mechanic that is critical to the gameplay - the Team-Up Counter. The player can counter a Team-Up attack by inputting the same command as their opponent, at which time a short fight sequence occurs separate from the main fight. If the countering player is able to land a successful hit in this “mini-fight” before the timer expires, the Team-Up will be canceled and the game switches back to the main fight. If the countering player is unsuccessful at countering, the Team-Up attack continues as normal.

Team-Up and Party-Up attacks are linked to a “Vigor Meter” which builds as players fight. Team-Up attacks cost two meter levels, Party-Up attacks cost five levels (the maximum available). A failed Team-Up cancel costs one meter.

Players choose characters who are students and teachers from a variety of fictional schools in Japanese cities. Each character has an aesthetic and fighting style linked to their chosen academic or extracurricular pursuits. For example, Ran from Taiyo School hopes to be a photojournalist and works at the school newspaper. Naturally her attacks feature cameras and photography, and her catchphrase is “This is a scoop!” Yurika from Seijun School is an aspiring musician and her fighting style heavily weaponizes the violin.

The Japanese version of the game includes a character creation mode which is played as a boardgame during an inter-school festival. Unfortunately this mode was not included in any non-Japanese releases due to the prohibitive time and cost involved in translation and localization. Instead of this mode, several unlockable sub-characters are included, built from the character creation elements in the Japanese version.

Story Elements

In Project Justice’s story mode, various colorful characters from numerous schools throughout Japan fight together (and each other) in order to thwart an evil ninja’s insidious plot to rule all of Japan. It’s a categorically ridiculous plot, but one that is easy to allow ourselves to fall into since it’s presented with such earnestness. The characters are invariably anime/manga archetypes, but those of us who grew up loving anime and manga will find joy in these characters’ motivations, struggles and triumphs. They are charming and endearing, well-drawn and well-animated.

The plot is explored in Story Mode. In this mode, the player selects one school at the start and plays through a storyline with a limited group of two to six characters (these are chosen at the beginning of each fight). 2D cutscenes move the story along before and after each fight, and depending on outcomes of certain fights or decisions made by the player, the stories can branch off to different paths. These determine which story elements the player sees and which fights occur. After defeating the boss, the player enjoys the ending for the chosen school’s story. The complete story isn’t revealed until every school’s story mode has been completed.

Legacy

Due to its late lifecycle release and relative rarity, the North American version is extremely expensive today. Complete examples routinely fetch between $300 and $400 on eBay. For this reason, Project Justice is likely out of reach for many casual retro gamers. Luckily there are plenty of YouTube playthroughs of this excellent game.

Project Justice is (sadly) a long-dormant franchise. Though it saw new life published as a comic in 2006, the game’s characters haven’t appeared in any other media since. Hideaki Itsuno has expressed an interest in reviving the series, but nothing has developed beyond these comments and there’s no indication that the series will return.